Program Overview

Energy Performance Contracting (EPC) provides an alternative procurement method for design and construction services that reduce facility operating costs through energy conservation improvements. EPC is an attractive financing model that uses cost savings from the project to finance the construction work, sometimes with no upfront cost. Also, all EPC projects must be done using a qualified Energy Service Provider (ESP) whose qualifications have been vetted by the State; this helps ensure the ESP maintains a high standard of technical expertise and has sufficient financial resources to guarantee cost savings for project financing.

EPC offers a smart way to make energy improvements to public facilities even when there is no budget to fund the work. The public entity contracts with an ESP to identify and install cost-effective improvements and to guarantee the energy cost savings. The ESP can also facilitate financing for the project, where the financing is repaid from the energy cost savings.

EPC offers many benefits:

- Potentially no upfront cost

- Guaranteed energy cost savings

- ESPs can offer information on project financing

- Single point of contact / accountability

- Curbs volatile energy prices and long-term rising costs

- Addresses deferred maintenance

- Improves productivity via better air quality, lighting, and temperature control

Energy Performance Contracting Contacts

Energy Resource Professional

Bonnie Rouse (406) 444-4956

What is Energy Performance Contracting?

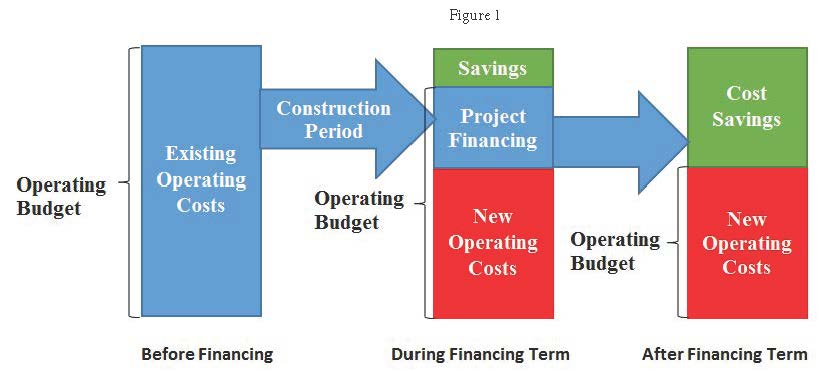

Energy Performance Contracting (EPC) is a construction procurement method where an Energy Service Provider (ESP) makes efficiency upgrades to your facility that yield cost savings from energy or water conservation. Ideally these cost savings are sufficient to pay for the total project cost which is typically financed over a 15 to 20-year term. The “Performance” term in “EPC” means the ESP measures and verifies the savings guaranteed in the contract are realized. Any difference between the measured savings and the guaranteed savings will be paid to you by the ESP. Figure 1 illustrates how the initial net savings increase once the financing is paid back.

EPC project cost savings typically come from cost-saving measures (CSMs) by upgrading to more efficient equipment or controls, some example CSMs include:

- LED Lights

- Occupancy sensors

- Boiler replacements

- HVAC Improvements

- New pumps, fans & drives

- Equipment controls

- Building envelope changes

- Water efficiency equipment

- Renewable energy installations

- Street, traffic & other outdoor lighting

Celebrating the Wins: Overview of Montana’s EPC Investments and Savings

- 27 Projects with 2015 Completion Date

- 3 Hospitals/Healthcare Facilities

- 7 Universities

- 17 K-12 Public Schools

- Total Investment $50,835,356

- 552 job years created ($92,000 = 1 job year)

- 20 Projects with complete data

- Total Investment $28,503,597 (financed + non-financed)

- 7,60,156 kWh/year

- 257, 099 MBTU/year

- 4,970,000 water gallons/year

- $864,029/year

Prequalified Energy Consultants

The pre-qualified list for energy performance contracting is applicable from 2025 - 2029.

| Consulting Company | Contact Name | Address | Phone |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ameresco, Inc. | Brian Solan |

7 W 6th Ave, Suite 605 Helena, MT 59601 |

(406) 461-7432 |

| Iconergy, Ltd | Doug Hargrave |

1905 Sherman St, Suite 1040 Denver, CO 50203 |

(303) 246-4967 |

| McKinstry Essention | Kris McKoy |

620 W Addison Missoula, MT 59801 |

(406) 214-3503 |

| Apollo Solutions Group | Mike Fuentes |

1133 W Columbia Dr Kennewick, Wa 99336 |

(509) 413-6227 |

| Willdan Energy Solutions | Mike Enzler |

5660 Lonesome Dove Ln Lolo, MT 59847 |

(406) 493-4062 |

| Consulting Company | Contact Name | Address | Phone |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ameresco, Inc. | Brian Solan |

7 W 6th Ave, Suite 605 Helena, MT 59601 |

(406) 461-7432 |

| CTA Helena | Rick DeMarinis |

316 N Last Chance Gulch Helena, MT 59601 |

(406) 495-9400 |

| E/S3 Consultants, Inc. | Steve Hastings |

P.O. Box 4595 Englewood, CO 80155 |

(303) 478-3729 |

| JE Engineering | Cindi Jarvix |

690 N Meridian Rd Kalispell, MT 59901 |

(406) 257-3013 |

| McKinstry Essention | Kris McKoy |

620 W Addison Missoula, MT 59801 |

(406) 214-3503 |

| MKK Consulting Engineers, Inc. | Kevin Pope |

175 N 27th St Suite 1312 Billings, MT 59101 |

(406) 545-6426 |

| National Center for Appropriate Technology | Stacie Peterson |

3040 Continential Dr Butte, MT 59702 |

(406) 494-4572 |

| River City Engineering | Laura Howe |

P.O. Box 1322 Florence, MT 59833 |

(406) 241-2863 |

| Consulting Company | Contact Name | Address | Phone |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ameresco, Inc. | Brian Solan |

7 W 6th Ave Suite 605 Helena, MT 59601 |

(406) 461-7432 |

| Coffman Engineers | Canaan Bontadelli |

2011 N 22nd Ave Suite 4 Bozeman, MT 59718 |

(406) 582-1936 |

| Con'eer Engineering | Jeff Gruizenga |

1629 Ave D D7 Suite 7C Billings, MT 59102 |

(406) 252-3237 |

| CTA Helena | Rick DeMarinis |

316 N Last Chance Gulch Helena, MT 59601 |

(406) 495-9400 |

| DC Engineering | Tom Wolgamot |

123 W Spruce St Missoula, MT 59802 |

(406) 829-8828 |

| Elkhorn Commissioning Group | Lagan Todd |

P.O. Box 11826 Bozeman, MT 59719 |

(406) 210-0655 |

| E/S3 Consultants, Inc. | Steve Hastings |

P.O. Box 4595 Englewood, CO 80155 |

(303) 478-3729 |

| Facility Dynamics Engineering | Mark Arney |

6760 Alexander Bell Dr #200 Columbia, MD 21046 |

(720) 317-7726 |

| Iconergy, Ltd | Douglas Hargrave |

1905 Sherman St #1040 Denver, CO 80203 |

(303) 246-4967 |

| McKinstry Essention | Kris McKoy |

620 W Addison Missoula, MT 59801 |

(406) 214-3503 |

| MKK Consulting Engineers, Inc. | Kevin Pope |

175 N 27th St Suite 1312 Billings, MT 59101 |

(406) 545-6426 |

| River City Engineering | Laura Howe |

P.O. Box 1322 Florence, MT 59833 |

(406) 241-2863 |

Documents

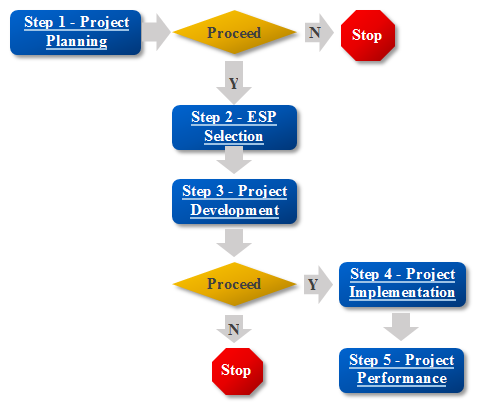

Step 1 - Project Planning

Step 2 - Energy Service Provider Selection

Step 3 - Project Development (Investment Grade Audit Stage)

Step 4 - Project Implementation (Energy Performance Contract Stage)

- Energy Performance Contract

- EPC Contract Attachments: Schedules & Exhibits & Risk Matrix

- Commissioning Guidelines for EPC

- Completion Checklist

- Project Summary Report

Step 5 - Project Performance (Measurement & Verification Stage)

Funding & Financing

Funding Options

Funding involves a source of money that does not need to be repaid, such as a capital budget allocation.

Capital Budget Appropriation - Investing funds in an EPC project that will generate a positive return should be an attractive opportunity, but too often there are competing demands for funding that are considered more urgent, critical, and visible. Still, it may be worth exploring the possibility with your organization's finance people.

Operating Budget Allocation - Obtaining a large allocation from your entity's operating budget may be difficult, but again, it may be worth discussing the idea with your finance department.

Utility Rebates and Incentives - Utility rebates may cover a portion of the project cost, and every bit helps. The resulting reduction in the amount that needs to be financed may allow for deeper and more comprehensive improvements. NorthWestern Energy and Montana Dakota Utilities offer a variety of rebates and other incentives through their Commercial Energy Efficiency Programs. For more information see the DSIRE database (filter for Program Type = Rebate Program) and/or contact your utility.

USDA REAP Energy Audit and Renewable Energy/Development Assistance Grant - These REAP EA/REDA grants of up to $100,000 are for local and state governments and higher education institutions (not K-12 schools). To learn more, visit the DSIRE REAP EA/REDA Grant page.

Montana Department of Natural Resources Wood Energy Program - These grants of up to $3,500 are for pre-feasibility assessments for wood biomass energy systems. See the Montana Department of Natural Resources Wood Energy Program web page.

Financing Options

Financing does need to be repaid, but the payments can be covered by the cost savings from the improvements. The ESP can offer information on how financing is generally managed for EPC projects, and your finance people will likely have preferences for how to finance the work.

ESP-Facilitated Financing - One feature of EPC that the ESP can bring to the table is their relationship with financial partners who are interested in financing good projects. The financing will typically take the form of one of the options below. It may not be the lowest cost option, but the convenience of working with a lender who is comfortable with performance contracting and the ESP makes this a frequent choice

Tax Exempt Lease Purchase (TELP) Agreements - Also known as municipal leases, these are perhaps the most popular option for financing performance contracting. Further, the effective interest rate is reduced because interest payments received from the government are exempt from federal income tax. In most states, TELPs are not considered debt and rarely require public approval. If funds are not appropriated to pay the lease in future budgets, the equipment is returned and the lease is terminated. For this reason, these leases are usually limited to equipment that is essential to the operation of the entity. To learn more, see this US DOE web page on Leasing Arrangements.

Capital Leases - Capital leases are common in performance contracting. The lessee (the entity using the equipment) assumes many of the risks and benefits of ownership, including the ability to expense both the depreciation and the interest portion of the lease payments. The equipment and future lease payments are shown as both an asset and a liability on the lessee’s balance sheet, and the lease payments are classified as capital expenses. Capital leases often have a “bargain purchase option” that allows the user to buy the equipment at the end of the lease at a price below market value.

Operating Leases - In these leases, the entity providing the equipment retains full ownership, so it does not appear as an asset or a liability on the user’s balance sheet. This can appeal to users that are near their borrowing capacity. There are specific IRS rules regarding when a lease can be treated as an operating lease versus a capital lease. Payments on an operating lease are usually less than for capital leases and loans, since the lessor owns the asset and the user is not paying to build equity. It is assumed that the residual value of the asset can be recovered at the end of the lease. Because of this, operating leases are typically limited to equipment with substantial residual value.

Montana Alternative Energy Revolving Loan Program - This program, administered by Montana DEQ, is for local governments, schools, and universities. Loan amounts of up to $40,000 are available on up to 10 year terms at a low interest rate (3.25% in 2017). Up to 20% of the loan can be for energy efficiency, with the rest being renewable energy. To learn more, go to the DSIRE Alternative Energy Revolving Loan Program web page.

Revenue Bonds - These are bonds with repayment tied to a specific revenue or cost savings stream. For example, cost savings from an EPC project can be pledged to pay off a bond. Because the bond issuer’s repayment obligation is limited to a specific revenue stream, revenue bonds are often viewed as higher-risk than a general obligation (GO) bond that can be repaid from general tax revenues, resulting in a higher interest rate cost. Revenue bonds may or may not require voter approval. See this US DOE web page on Bonding Tools.

5 Step EPC Process

The 5-Step EPC Process

- Provides guidance for evaluating an Energy Performance Contract (EPC) as a procurement option at your facility.

- Helps you select an Energy Services Provider (ESP).

- Is the Investment Grade Audit (IGA) phase where the ESP conducts a thorough and complete analysis of cost savings opportunities.

- Is the Energy Performance Contract (EPC) phase where the ESP installs cost saving equipment.

- Is the performance stage (also part of the EPC contract), where the ESP compares post-project measured savings to the projected guaranteed savings.

In Steps 3, 4, and 5 the ESP provides services under contract.

The purpose of this step is to help you determine if energy performance contracting (EPC) is an appropriate procurement path for your needs. In this step you will compile data to assess cost-saving opportunities for a project, review available resources, and identify stakeholders for your project team. If you’re already communicating with an Energy Service Provider (ESP), they will likely be willing and able to help with some of these activities.

Learn about EPC Resources Available from DEQ

Contact our Energy Bureau to let us know of your plans for energy performance contracting. We can help you follow the state statutes and provide free technical review to help you get your project set up and avoid potential project pitfalls.

Communication is a key element throughout the EPC process. The process relies on you, the ESP, and our team for planning and reporting project activities. It is important to keep us informed early and throughout the process to ensure a successful EPC project. We are capable of providing assistance and technical review for all aspects of the EPC process.

Identify Potential Projects

Next you will determine if your facilities are a good fit for EPC based on potential project size, annual utility bills, comfort or maintenance problems, equipment age, funding options, and future plans for renovation or retention. An ESP may be helpful in assisting with this process.

Some guidelines related to cost savings and project size may be helpful in the pre-screening process. Here is an example:

- Determine utility consumption and costs on an annual basis. You’ll need at least the last 12 months of utility bill data, and three years is preferable. As an example, let’s assume your utility costs are averaging $100,000 per year.

- Utility cost savings for most EPC projects typically do not reduce your annual utility bills by more than 30 percent. A bill reduction range of 15-25 percent is common. In our example, assume the potential savings are 25 percent, or utility cost reduction from $100,000 to $75,000 per year.

- Depending on the financing source, the finance term is typically 15 or 20 years. 20 years is the maximum set by Montana law. If we assume 20 years, this means your annual cost savings of $25,000 per year could cover financing payments totaling $500,000 ($25,000/year * 20 years).

- The $500,000 in available financing includes financing costs such as interest, so the project itself will need to cost less than $500,000. A rule of thumb is the principal portion of the payments (the portion that pays back the cost of the project) will amount to 80 percent of the financing payments. So in this case, the principal payments would equal $400,000 ($500,000 * 80%).

- Based on these assumptions, a facility with $100,000 in annual utility costs could potentially support a $500,000 financing package with a total EPC construction cost of $400,000.

For another guideline, our two-page Is EPC Right for Me? document will help you compare your facilities’ energy use to others and consider other important factors. The US Department of Energy (DOE) also offers a series of benchmarking sheets that show the average project statistics in several public market sectors.

Our Preliminary Assessment Workbook will help you through the process of identifying potential projects. This Excel-based tool helps you compile and organize general building information and utility data to assess energy savings potential. The workbook also provides baseline information your ESP will request from you as the project progresses.

Begin Outreach to Key Stakeholders

Support from multiple stakeholders is critical to a successful EPC project. Key staff may not be familiar with EPC, so gaining their support may take some time. Meet with them now to introduce EPC and its benefits, let them know what you’re doing, and lay the groundwork for their support. The following two US Department of Energy (DOE) one-page handouts may be helpful in these meetings:

It is important to identify and get your key stakeholders involved early in every EPC project. We recommend developing both an internal and external stakeholder team. Key internal stakeholders listed below are described by function, since the names of the departments with these functions often vary:

- Authorizing Power (Mayor, City Council, School Board, etc.) – These are the people who will ultimately need to approve the project. They share many of the same interests as the stakeholders below.

- Finance Function – A financial officer will sign off on the project; get this person involved early. This is a good time to discuss all possible financing options and get a feel for what might work. Finance people will tend to focus on the cash flows and risks, so the performance guarantee and the financial strength of the ESP will be of particular interest.

- Budget Function – Your budget officer will be responsible for managing the budget and payments to the ESP. Although the EPC project will reduce your utility cost, a new account is needed to transfer these cost savings toward repayment of the project financing. Budget staff will ensure that the combination of your post-project utility costs plus project financing payments will be less than or equal to your pre-project utility costs.

- Legal Function – The project will be governed by two contracts: the Investment Grade Audit (IGA) and project proposal contract followed by the Energy Performance Contract. The legal function will need to approve both contracts while also ensuring you follow EPC program statute and rules.

- Contracting/Purchasing Function – This party will typically need to be involved in the "Request for Proposal" process when selecting an ESP.

- Facilities Function – Staff responsible for operating and maintaining the buildings to be improved know the most about the facilities and will take lead roles working with the ESP.

Key external stakeholders should include your utility provider, the State Energy Office, and your selected ESP:

- Utility – Your gas, electric, and water utilities representatives frequently provide rebates, grants, or other incentives for installing energy-saving equipment. It’s important to discover what incentives are available early in the process, since this revenue can augment project financing and can have an impact on the potential size of the project.

An important factor in winning project support is to tailor your outreach to the audience, speaking their language and highlighting the benefits most likely to be meaningful to them. For instance, in talking with finance people, you will want to lead with financing benefits (long-term reduction in operating expenses, financing options that are not treated as debt, etc.). US DOE’s EPC Opportunities and Advantages offers additional credibility.

Define Project Goals

Next define and outline your project goals. Common EPC goals focus on project components that have cost-savings measures targeting reduced energy or water consumption or reduced operating and maintenance costs. Common goals include:

- Energy cost savings

- Operating cost savings

- Maintenance cost savings

- Positive cash flow (cost savings exceed financing and other costs)

- Attractive financing that avoids the need for capital or additional operating budget allocations

- Inclusion of a critical non-energy capital improvement in the project, with cost savings from the energy improvements helping to pay for the non-energy improvements

- Heightened awareness of occupants about energy waste

- Resolution of deferred maintenance issues by replacing old equipment before it fails and disrupts operations

Keep in mind the interests of your stakeholders and supporters. While most project goals should be quantified, it may only be feasible to give rough estimates or ranges at this stage of project development.

If you’re not already talking with an ESP, it’s never too soon to begin identifying ESPs that might be interested in working with you, and to reach out to them for input. They may be able to help with identifying realistic goals. Keep in mind that Montana law requires you to solicit proposals from at least three qualified ESPs so this is a good time to begin finding a project partner.

Explore Financing Strategies

The goal at this point is not to nail down financing, but to simply explore what financing options might be available. You’ll want to talk with your finance and budget departments to learn the possibilities. US DOE’s guide on How to Finance an EPC may also be helpful.

The options fall into two categories: funding and financing. Funding involves a source of money that does not need to be repaid, such as a capital budget allocation. Financed revenue will be repaid from the project cost savings improvements. ESP’s can offer information on how financing is generally managed for EPC projects, and your finance people will likely have preferences for how to finance the work.

It’s important to note that you will need to be ready to pay for the IGA if the project does not go beyond the IGA phase (e.g., the IGA determines that a project is not viable or you decide not to proceed for some other reason). In most cases, the cost of the IGA is folded into the overall project cost and financed or funded accordingly.

Choosing a payment option is not an either/or question. It may make sense to use funding sources to pay for a portion of the project and to finance the rest. You can even choose to break your project into deferred maintenance and energy savings categories and procure construction through a bid and EPC separately. Funding sources for deferred maintenance or break-out projects can be especially useful for funding measures that might not be well-suited to financing, such as those with longer paybacks. Even a relatively small capital budget appropriation will help, and once your finance people get some experience with EPC, they may be more comfortable with a larger project the next time.

Although funding through a capital budget allocation may be preferable to long term project financing, financing is required for at least a portion of the project to qualify as an EPC in Montana. Work with your finance people to get a feel for which options might be suitable for your circumstances. To view potential financing options please visit the EPC Funding and Financing Information page.

Develop Scope of Potential Work

Next, collect more detailed information about your facility to include in the Request for Proposal (RFP) you will issue to select an ESP from the pool of pre-qualified ESPs. The goal here is to attract ESPs by providing them with an idea of what your project might involve. You may have already collected much of this information using the EPC Preliminary Assessment Workbook. If not, now is the time to do so.

Start with the buildings that are most likely to have savings opportunities that justify an EPC project. The information to collect includes details such as:

- Buildings: age, size, as-built construction drawings and specifications, and drawings from any renovation projects.

- Equipment: age, make, model numbers, efficiency ratings, and service records for major equipment, including HVAC, lighting, hot water heaters, and plug loads (computers, copiers, desk lamps, etc.), giving special attention to older and less-efficient equipment.

- Utility information: list utility service providers, account numbers, meter locations, and energy use for at least 12 continuous months, and preferably for the last three years.

- Potential improvements: identify and list potential improvements based on equipment age, efficiency ratings, maintenance problems, etc.

Decision Point #1 - Continue?

You should now have enough information to decide whether to move forward with selecting an ESP to perform an IGA. Important questions to answer at this point include:

- Will the likely energy cost savings support repayment?

- Are you confident that funding or financing can be arranged?

- Can your entity pay for an IGA if the project does not move beyond that point, (e.g., the IGA determines that a project is not viable or you decide not to proceed for some other reason)?

- Does the project have the support of the necessary stakeholders?

- Do you have the resources required for the RFP process?

- Have any ESPs expressed an interest in the project?

If the answer to all of the above questions is "yes," congratulations! The next step involves selecting an ESP and negotiating the project contract terms.

If you have decided to proceed with an Energy Performance Contract opportunity identified in the previous step, next you will select an Energy Service Provider (ESP) from the pre-qualified list.

Develop Request for Proposal (RFP)

Using the RFP - Request for Proposals template, you will gather and organize information about the facility and proposed improvements to complete Attachment A: Technical Facility Profile in the RFP. The information includes utility use and cost history; completed upgrades; plans for renovations or changes; comfort and maintenance issues; capital needs or funds available; desired outcome; and other pertinent details about the proposed project.

The other attachment, Cost and Pricing Proposal, will be filled in by the ESPs who respond to the RFP. It requests only general information; the intent is to select the ESP based on qualifications and suitability for the needs of your entity. The only cost information suggested is contained in Attachment B: Cost and Pricing Proposal in the RFP.

You may want to consider developing the RFP to consider multiple phases based on the facilities to be included in the overall project. This is particularly useful for larger campuses or entities with multiple facilities. The benefits for phasing include:

- One RFP to select the ESP to provide services to all facilities

- If your entity is dissatisfied with the selected ESP or wishes to re-open the process to other ESPs, you can issue a new RFP for subsequent phases

When considering phases, it is important that the RFP contain language defining the initial scope of work (facilities) and references that the scope may include additional facilities.

If this language is not included, then a new RFP will be required for additional phases or facilities. The RFP must be sent to at least three ESPs on DEQ’s Prequalified ESPs list.

Prior to the response deadline, your entity may host pre-submittal informational meetings. During these meetings, you’ll describe the proposed project, review pertinent information, conduct walk-throughs of the appropriate buildings, and otherwise answer any outstanding questions.

In return, the ESPs that have been contacted are expected to respond to the RFP. Appropriate responses include submitting a proposal or sending a letter declining participation in the project. Failure of a contacted ESP to respond is unacceptable and could potentially result in the ESP’s removal from the EPC program.

Select Energy Service Provider (ESP): Pre-qualified List

Depending on the number of responses, the exact nature of the evaluation process may vary. In general though, you should review the ESPs’ submissions and develop a short list of ESPs you wish to interview.

The U.S. Department of Energy’s EPC – How to Select an ESP and Evaluation Workbook documents offer helpful background for this process, as does ESC’s ESP Evaluation Sheet.

You will want to evaluate qualifications based on, but not limited to, the following capabilities and criteria:

- Quality of technical approach

- Experience with:

- Design, engineering, installation, maintenance, and repairs associated with cost-saving measures

- Overall project management

- Projects of similar size and scope

- Post-installation measurement and verification of guaranteed cost savings

- In-state projects and Montana-based contractors

- Commissioning of projects

- Training of building operators

- Conversions to a different fuel source

Please note that price or cost is not a part of the selection process. This is due to the fact that the project scope is likely not fully developed to allow the ESP to put together a bid at the time of the RFP. Experience indicates that it is best to negotiate fees with the selected ESP at a later point. However, it is advisable to request some basic pricing information (e.g., ranges of percentages of total project costs on typical projects) to assist in your comparison of different ESPs. Ultimately, the main objective of this process is to select the ESP that is best able to meet your specific needs based on experience and qualifications rather than lowest cost.

You will then interview the shortlisted ESPs. The ESP’s interview team must consist of the individuals that will be assigned to the project. The ESP should be prepared to present in detail the criteria above which will be evaluated according to the Montana rules and legislation.

After evaluation of the interviewees, you’ll need to decide whether to:

- Select an ESP

- Decline to select one of the interviewed ESPs and re-open interviews with non-short-listed ESPs or

- End the selection process and put the project on hold for some period of time.

Before continuing, it’s important to consider again whether your organization has the funds available to pay for an Investment Grade Audit (IGA) if the project does not move forward and there are no energy cost savings to pay for the IGA. If not, it may be advisable to delay entry into the EPC process as there are times when the process does not move beyond the audit stage. In such cases, the cost of the IGA must then be absorbed in full by your organization. Assuming that the project does move forward, the costs of the audit may be rolled into the EPC or paid directly using these budgeted funds.

Negotiate Investment Grade Audit (IGA) Contract

You and your chosen ESP will now need to determine an agreed-upon project scope, including which buildings will be audited, total square footage, and overall price for the IGA and project proposal. The IGA - Investment Grade Audit and Project Proposal Contract can serve as an objective third-party template to help facilitate the process of reaching agreement.

The IGA Price Guidelines may also be helpful in providing a sense of the typical costs of an IGA for various facility types. Please note that the prices are only a guideline range. Depending on the situation, costs may increase by up to 50 percent.

During the negotiation phase, you may provide the ESP with general information regarding plans, needs, problems and other factors that may affect the IGA. This information is beneficial to the ESP in developing its approach to the IGA and the EPC process as a whole. You or the ESP may have specific measures you would like evaluated in the IGA; however, the audit should look at all cost-saving opportunities.

If you are unable to negotiate a satisfactory contract with the selected ESP, negotiations with that firm should be formally terminated so that negotiations can begin with the next most qualified provider. The contract should be submitted to DEQ for review prior to signing. The ESP is responsible for sending an electronic copy of the fully executed contract to DEQ.

Next, your selected ESP will conduct an IGA and deliver a project proposal. If you decide to proceed at that point, you’ll nail down the details and sign a contract with the ESP to perform the work.

Investment Grade Audit (IGA)

The IGA is an interactive process between your organization and the ESP. The ESP gathers and analyzes information and presents its findings to you throughout the IGA process. In return, it is in the best interest of your organization to ensure that the ESP has access to the information and facilities needed to gather the required data.

The IGA process serves as the foundation of EPC and is critical to the success of the project. The data collected during this process is essential to determining baseline consumption, cost-saving measure (CSM) savings, and actual savings.

Initial Analysis

The ESP conducts a preliminary analysis of your facility in which the ESP staff will collect data and background information related to facility operations and energy use for the past three years. This initial survey will involve a variety of activities including interviews with the facility manager(s), staff, and building occupants, as well as a review of all major energy-using equipment. If necessary, the ESP will also perform “late-night” surveys outside of normal use hours to confirm system and occupancy schedules. Your entity will need to accommodate all reasonable requests made by the ESP in pursuit of gathering quality usage data. From this survey, the ESP will develop and deliver an initial analysis, identifying potential cost-saving measures in your facility (regardless of cost-effectiveness), a project baseline, and cost and savings estimates. Furthermore, this report should detail the potential for the successful development of an EPC and provide a brief list of recommended CSMs for further analysis.

At this point you will want to determine whether these preliminary findings fulfill your organization’s requirements. If not, you may want to terminate the process according to the terms in the IGA contract. Keep in mind, however, that if you terminate you may remain responsible for the cost of the IGA as it has been performed to this point.

Further Analysis and Audit Report / Project Proposal

Assuming the initial findings do fulfill your needs, the ESP will then continue with the IGA, analyzing the agreed-upon measures, developing cost estimates, and identifying utility savings. The results of this analysis will then be compiled into a final report. The report will provide an engineering and economic basis for the negotiation of a potential EPC between you and the ESP. The report will include:

- A detailed description of your facility (i.e., existing equipment, systems, and conditions)

- Baseline consumption and rates for energy, water, and other utilities

- Detailed information regarding proposed cost-saving measures including estimated costs and guaranteed savings

- Preliminary commissioning and measurement and verification (M&V) plans

- Project cash flow analysis including guaranteed savings, O&M savings, M&V costs, and other economic factors regardless of guarantee status

It is recommended that you submit a copy of this report to DEQ for an independent review of the findings. Doing so will help ensure that the processes set down in the contract were fulfilled and that all energy and cost calculations, proposed improvements, and M&V plans are reasonable. Note that submission is mandatory if state funds are being used to finance the project.

Upon receiving the final report, you will need to sign and submit a copy of the Certificate of Acceptance for the IGA report to the ESP and DEQ.

Decision Point #2 – Continue?

Once the IGA report has been accepted, you will need to decide whether to proceed with an EPC or explore alternative means to complete the project or portions thereof. In most cases, you will move to the next step to begin implementation of measures identified in the IGA report. You have the option to:

- Proceed with the EPC as recommended in the IGA report

- Proceed with the EPC with modifications (possibly reduced scope) to keep the project within the financial ability of your entity or requirements of Montana’s EPC program

- Terminate the EPC process and proceed with implementation of measures through design-bid-build or other construction process. At this point the savings guarantee is terminated. An alternative procurement method may also be required as the EPC procurement method is only permitted for EPC projects.

- Terminate the EPC and do nothing.

The IGA contract specifies a timeframe for your decision of whether to proceed to the EPC. Typically this period is 90-120 days. If you decide to terminate the EPC process at this point, your entity will be responsible for paying the ESP for the IGA under the terms specified in the IGA Contract.

Decide on Scope of Project

Assuming you’ve decided to proceed, you will work with the ESP and your owner’s representative to scope the project. Factors to consider in this process include:

- How big a project is your entity interested in taking on?

- Are there any funding/financing limitations on amount or term?

- Are there any non-energy upgrades that you want to include?

- Do you want the ESP to take responsibility for operation and maintenance?

One of the more complex questions involves the varied payback periods of different cost-saving measures (CSMs). CSMs with shorter paybacks, like lighting, are easy to justify and will be feasible with 5-10 year financing. Longer paybacks may require up to the maximum of 20-year financing. CSMs with even longer paybacks can often be justified by looking at the combined payback period for all the CSMs. For instance, if one CSM has a payback period of five years, and another CSM of equal cost has a payback period of 25 years, the combined payback is less than mine years. Your finance people, ESP, and owner’s representative will be familiar with the interplay of payback periods, loan terms, and other factors that may have a bearing on which measures to include.

Decide on Funding and/or Financing

You’ll want to work closely with your finance department to make the final decision of how to pay for the project. Your ESP may also be able to offer helpful information on how financing is generally managed. Alternatively, you may decide to issue a financing solicitation in order to introduce competition. US DOE’s Solution Center includes a Model Documents for an Energy Savings Performance Contract Project page that includes a Financing Solicitation section with templates at the bottom of the page.

Decide on Measurement and Verification (M&V) Plan

M&V is crucial to all EPC projects, so the plan for M&V should be set as early as possible in the project for the greatest success. The purpose is to accurately measure whether the improvements are delivering the guaranteed energy savings. The cost for M&V is included in the overall project cost and is paid for by the entity during the initial monitoring period (minimum of three years in Montana). M&V needs to follow the guidelines established in the International Performance Measurement and Verification Protocol (IPMVP). See Measurement and Verification (M&V) Guidelines for more information.

A strong M&V plan should define precisely what “energy savings” means, and specifically how savings will be measured. Furthermore, the M&V plan should address how unforeseen events (weather variations, building use changes, etc.) are to be handled. Typically, a preliminary M&V plan will have been developed during the IGA process with a finalized version developed as a part of the EPC contract process. In general, a good M&V plan should:

- Identify and establish utility baselines for the project

- Identify appropriate M&V options for different cost-saving measures that are in line with your project goals

- Specify quality control procedures for data collection and timely performance monitoring

- Provide cost-effective M&V methods to verify project performance.

Negotiate Contract with ESP

You will want to use the Energy Performance Contract and EPC Contract Attachment: Schedules & Exhibits as templates. It’s important you understand each part of the contract and the services to be provided. The contract should be reviewed by your legal staff. Be sure open-book pricing is included to ensure you receive good value.

The guarantee is the cornerstone of an EPC contract. It covers the annual debt service and requires the ESP to pay any remaining balance if expected annual savings are not achieved.

In addition, be sure to review maintenance requirements and services. In order to guarantee performance or savings, an ESP often requires maintenance on new equipment. Additional services can include reviewing operational strategies, reporting on equipment operating problems, and repairing and replacing equipment.

Prior to signing, you will need to submit the EPC to DEQ for review. For state-owned facilities, DEQ may forward the contract to the Architecture and Engineering Division. The ESP is responsible for sending an electronic copy of the executed contract to DEQ. The ESP will also work with you to develop a marketing overview of the project for sharing as part of DEQ marketing efforts.

In this step, the ESP will install the improvements and may provide other services as part of the project.

Cost-saving Measure (CSM) Installation

Once the EPC contract is signed, the ESP will complete the design of the retrofit work and obtain your approval to move forward with installation. Following installation, the ESP will update the counts, runtime, and other assumptions to match installed conditions and issue a Post-Installation Report. This required report provides the final, as-built cost and savings figures.

Commissioning

Commissioning refers to a quality control process that allows for the achievement, verification, and documentation of a building’s energy performance to ensure it meets defined requirements. Buildings should be commissioned when they are first constructed and after substantial changes are made. Recommissioning involves commissioning a building that was previously commissioned to make sure that it is still operating optimally. Retro-commissioning refers to the process of commissioning a facility that may not have been previously commissioned.

Commissioning is an important process in any EPC project. It ensures that the installation is complete and functioning as intended under various loads and conditions. While commissioning may be completed by the ESP or an independent third party, it is important you also be present for checkout and testing. Commissioning is a prerequisite for substantial completion of the project. See Commissioning Guidelines for EPC for helpful suggestions.

Effective commissioning requires that your organization and the ESP identify your facilities’ specific requirements during project design and develop a clear plan to meet them. In order to achieve this goal, it is critical that you maintain close contact and clear communication with the ESP throughout the design process to ensure the commissioning requirements are effectively incorporated into the specifications. Following the design development process, those requirements can then be used to develop the commissioning plan. Any such plan should include a commissioning schedule, all documentation requirements, and specific team member responsibilities.

It should be noted that commissioning costs can vary significantly depending upon the complexity of a project. Many investments in commissioning will pay back in less than three years via savings from avoided future costs such as equipment repairs or wholesale replacements. The value of commissioning has only increased in recent years as a result of increasingly specialized building systems that must be effectively integrated along with increasingly strict building and safety codes. The cost of commissioning is included in the overall project cost.

Training

As with any new equipment, facility staff (and in some cases the occupants) will need to be trained on proper operation and maintenance. The ESP is responsible for providing this training. The cost of this training can be included in the overall project cost.

Project Closeout

Verify the completion of each task using the Completion Checklist. When all the contract tasks are completed (installation, commissioning and training), you will sign and issue a Certificate of Acceptance for the Installed Equipment to signify that the work has been completed. A copy of this certificate will be provided to DEQ.

Optional – Operations and Maintenance (O&M) Services

Depending on the complexity of the equipment and other factors, the ESP may offer (for a fee) to operate and maintain the equipment. You may or may not find this advantageous in terms of outsourcing the work to very specialized experts and to maintaining the ESP’s accountability. If there are problems with the equipment, there would be no questions about whether your facility staff might be to blame for improperly operating or maintaining the equipment. The cost of O&M provided by the ESP is normally paid for much like the payroll for your facility staff – it’s a budgeted operating expense as opposed to a cost folded into the overall project cost.

In the last step, the ESP will monitor energy savings, deliver annual reports, and repair or reimburse you for any shortfalls in the guaranteed energy savings.

Monitor Project Performance

Following the successful installation of the agreed-upon improvements, the ESP will perform ongoing project monitoring for a minimum of three years per Montana’s statute. During this initial monitoring period, you and your organization will absorb all measurement and verification (M&V) costs associated with this monitoring. However, if it is ever shown that there is a shortfall in savings for any year within this period, the ESP must then pay for any additional M&V for the years following the initial period until:

- Guaranteed savings are met for consecutive years equal to the initial monitoring period, or

- You and the ESP can negotiate a settlement regarding the shortfall for all future years of the contract term.

During the initial period, it is required that the ESP complies in full with all requirements of the EPC as originally negotiated. These requirements should include (but not necessarily be limited to):

- Measurement and verification reporting and services

- Guarantee of performance and cost savings

- Maintenance and/or repair of equipment

- Training for facility personnel on maintenance and systems operations

- Training for occupants

Additionally, the ESP is required to supply both you and DEQ with a minimum of three annual M&V reports providing detailed information on the project and project performance.

Measurement & Verification (M&V) Protocols on Agreed-Upon Frequency and Basis

M&V needs to follow the guidelines established in the International Performance Measurement and Verification Protocol (IPMVP). For more complete information on how to apply the IPMVP, Department of Energy has developed the Federal Energy Management Program (FEMP) M&V Guidelines. See Measurement and Verification (M&V) Guidelines for more information on the M&V process and requirements for Montana. The ESP determines the units of energy and water saved by the cost-saving measures as well as any O&M cost savings due to the CSMs. These measured savings are then compared to the guaranteed savings to determine whether or not the savings guarantee has been met. If the measured savings are less than guaranteed, then the difference is multiplied by the baseline unit costs and any escalation rates included in the EPC, regardless of any guarantee of escalation rates.

For each year of the guarantee period, the ESP will submit the annual M&V report to you and send an electronic copy to DEQ. The format of the report is provided in the Annual M&V Report Outline. You and our office will review and provide comments to the ESP. The ESP addresses the comments, finalizes the report, and sends an electronic copy to you and our office. If the guaranteed savings are not met during any year of the guarantee period, the ESP shall pay your entity the difference between the actual (measured) savings and the guaranteed savings. If the guaranteed savings are not met for any year in the initial monitoring period, then the ESP is responsible for the M&V costs until guaranteed cost savings are achieved for a term of consecutive years equal to the initial monitoring period.

If the actual (measured) savings exceed the guaranteed savings in any year of the guarantee period, the excess savings shall remain with your entity. Excess savings may not be used to offset any shortfall in previous or subsequent years of the guarantee period.

Modifications to the M&V process during the guarantee period are limited to those mutually agreed to by you and the ESP. In the event of a shortfall, you and the ESP may negotiate the terms of M&V and the shortfall payment for the remainder of the EPC finance term.

You will need to inform the ESP of any significant changes in operation that could affect the savings calculations. The EPC contract should include a section that describes how potential changes will be handled during the guarantee period. Changes that may affect the savings calculations include:

- Operating hours

- Facility use

- Equipment (new, removed, or additional)

- Building addition, renovation, or demolition

- Occupancy

At the end of the guarantee period, the ESP will provide a summary report to DEQ that includes basic project information – cost, financed cost, savings, etc. – using a form provided by DEQ. The ESP may also work with you to develop a complete marketing overview of the project, including photos and quotes, for sharing as part of DEQ marketing efforts. The case story may be posted on the DEQ website for EPC and post project results.

FAQs

- What can the state do to help individual entities with the EPC process?

The state has developed standardized procurement, evaluation, and contracting procedures and documents (e.g., RFP, IGA contract, EPC contract, etc.). The state also offers free technical assistance and training to entity staff throughout the EPC process. For assistance, please contact DEQ staff. - What do entities need to know as they initially plan EPC project scope, energy-savings objectives, and financing terms?

Any project should be consistent with the site’s long-term master plan. Obviously a building slated for demolition during the likely term of an EPC should not be included in a project. A building scheduled for a major change in operation – such as converting a barracks building into office space – could necessitate a change in the way savings are calculated (baseline adjustment) at some point down the road. So it’s important to anticipate these changes and plan for them in the contract.

As for energy savings objectives, we encourage entities to be open to a wide variety of Cost-saving Measures (CSMs). They may have a desire to investigate certain technologies, and it’s important to include those in the RFP, but an ESP should be encouraged to develop a comprehensive project. That’s where their expertise lies – in their ability to perform assessments, find opportunities to save energy and water, and to develop comprehensive projects. The entity should also have a defined economic benefit or requirement for cost-effectiveness, such as the savings for the project must be able to pay for the project cost within 10 or 15 years.

Financing rates are generally not under the control of the ESP; they are subject to the same market forces that drive interest rates on other types of loans. These finance rates do affect the length of the performance period of an EPC, however. In general, the agency will maximize project investment and the savings delivered when the length of the performance period is maximized, subject to the statutory limit of 20 years (which includes the construction period). - How is an ESP different from a standard architectural/engineering firm?

An ESP provides a turnkey approach to design and implementation of an energy improvement project. This includes design (which may be in-house or contracted out) and construction management where the ESP serves as the General Contractor. An ESP must financially guarantee energy and operating cost savings by measuring project performance results over time. The ESP assumes a financial risk that the project will produce the promised savings performance. Also, the ESP typically provides a broader range of customer services, like measurement and verification of cost savings and commissioning of project equipment and systems. It provides more comprehensive engineering analyses of energy, water, and maintenance cost savings opportunities. It also assists in providing financing for projects. - How is an Energy Performance Contract (EPC) different from a standard equipment specification and bid project?

An EPC relies on the technical expertise of an Energy Service Provider (ESP) to design and build a comprehensive and creative technical energy project. The ESP provides a guaranteed maximum price, rather than lowest bid, which allows it to negotiate prices with subcontractors to achieve the savings objectives without compromising quality. Also, with an EPC you buy a guaranteed performance result, not just new equipment. These contracts contain a guarantee of avoided utility and operating costs, along with guarantees of environmental comfort parameters, such as temperature, humidity, and carbon dioxide levels. Specifically, they provide compliance with applicable American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) and Illuminating Engineering Society (IES) standards. - Why is a comprehensive EPC project preferable to several single measure projects?

A comprehensive approach maximizes the capture of savings opportunities available from a specific building or set of buildings. It also provides financial leverage to do more expensive individual measures that might otherwise not be economical to do on a stand-alone basis. A comprehensive project allows the measures with shorter payback periods to subsidize those with longer paybacks. A common error is for a facility to do only the shorter payback measures first and postpone more expensive upgrades. The agency has then lost the opportunity to bundle measures to maximize both energy and cost savings. - Why not just implement these comprehensive efficiency projects with our own technical staff and capital funds?

This is an option that you need to consider. Do you have the resources – time, finances and expertise – to complete the project? Are there competing demands for these resources? Is the savings guarantee important to your project? Many entities do not have adequate capital funds appropriated to address many of their capital equipment replacement needs. They also may not have enough staff or the appropriate technical expertise to manage these complex projects in-house. There may be little incentive for in-house staff to accept the risk of project non-performance or financially guarantee the results of the project’s performance. Agency staff may not have the expertise to measure and verify savings or commission the equipment. Also, the traditional procurement process for capital projects may require the acceptance of low-bid equipment instead of a best-value project design that minimizes life-cycle costs. The traditional capital budget process may require as long as five years or more to do a project that an ESP could deliver in less than three years. The savings opportunities that are lost by waiting three extra years or more for capital funds to implement efficiency projects creates a huge cost of delay. - If our agency has been doing small efficiency projects for many years, haven’t we already picked the “low-hanging fruit” of these savings and eliminated the opportunity for a comprehensive energy efficiency project?

While this may be true in some cases, many owners are finding that even though they have spent thousands or even millions of dollars over the last 10-15 years on energy efficiency projects, allowing an ESP to evaluate their facilities comprehensively often results in their finding large untapped savings opportunities. One reason for this is the continual evolution of energy efficiency technologies. Lighting technologies have improved dramatically in the last five years. Also, the technology of direct digital control systems has improved and the opportunities to save energy, especially in larger buildings with larger equipment loads, may allow these new controls to provide economically feasible savings. It is recommended that all facilities be evaluated against an Energy Use Index (EUI) of British Thermal Units BTUs per square foot in order to determine their relative efficiency compared to similar types of buildings. Projects that may not have been economically attractive five years ago may be feasible today due to the higher utility costs. - In Step 1, how do I evaluate whether my facility is a good candidate for an energy savings performance contract?

The guideline document “Is EPC Right for Me?” is a good start to determine if your facility is a good candidate for an EPC. This document provides guidance on determining if the savings potential exists that would support an EPC project. The second document, “IGA Price Guidelines” provides a general overview of costs associated with an Investment Grade Audit. Most ESPs prefer a minimum project size of at least $1 million, but some will often work with projects as low as $200,000. Also, equipment near the end of its useful life, which has very high maintenance and repair costs, indicates the potential for significant operating cost savings. If there are significant problems with the operational control of building comfort, this provides another opportunity to create value by dramatically improving indoor environmental quality. Due to the long-term nature of financing EPC projects, it is important that the agency have a long-term plan to use the building in the future. - What are the main obstacles to ESPs delivering EPC projects to state agencies?

Lengthy government procurement processes extend the implementation cycle that increases ESP project delivery costs and the cost of delay for agencies. Multiple agency decision-makers who need to approve projects can delay the process of finalizing the energy services agreement and project financing. The entity needs to establish an in-house team that is focused on selecting a project based on the best value rather than low bid. The entity's team should include the facility manager, budget and finance staff, legal advisor, procurement officer, engineering staff and outside technical consultants if applicable. The entity facility and financial managers receive little or no recognition or incentives for championing EPCs. Rather than combining several agency facilities into a single procurement, many building managers focus projects on either one or just a few buildings, which makes the project’s economics less attractive. Financing energy performance contracts over periods of less than 15 years erodes the opportunity to leverage financing for capital projects. - What are the main benefits of EPC projects?

The most obvious economic benefits are utility and maintenance cost savings. The modernization and replacement of aging capital equipment, however, is probably an even more important project driver. Significant improvement in the indoor environmental quality resulting from better control of temperature, humidity, and ventilation is another benefit. Preserving scarce capital funds for priority projects that do not produce significant operating cost savings is an additional and important financial benefit. - What can I do to improve the EPC process and outcome for my project?

Identify a leader within your organization to carry the project and assign a support team including administration, finance, legal and operations. Determine a general understanding fof your facility needs, project goals, financial ability and economic requirements for the project. Include DEQ in the process through communication and the use of program documents. Develop a partnership ethic that emphasizes cooperation and clear understanding of each party’s roles and responsibilities. Full and timely communication between all relevant entities and ESP staff is crucial to project success. Keep good records of revisions to the project scope as the project evolves so no one is surprised at the final project scope. It is important to budget realistically for project commissioning, training, maintenance, and measurement and verification services. Making quality decisions at every step of the process will produce high quality project results. Review and approve a detailed plan for measuring project performance, including the role of agency staff in providing notice of building changes and utility data to the ESP. Consistently apply realistic standards and fairness as you negotiate the allocation of project responsibilities between the entity and the ESP. - When does EPC make the most sense?

EPC makes the most sense when facilities contain aging equipment that is nearing the end of its useful life, or when the buildings and central plant equipment have not received an Investment Grade Audit within the past five years. Newer equipment generally has higher efficiency, and it will also have many years of service left, so there is less economic benefit to replacing it. - What are the most common challenges for agencies pursuing an EPC for the first time?

General construction: EPCs are generally major construction projects and, as in other construction projects, you never really know what is behind the walls. There can be surprises at any stage of construction. Beyond that, the entity must have the expertise and manpower to manage a construction project occurring on their installation: approving schedules, providing building access, reviewing construction drawings and commissioning reports, and inspecting equipment installation prior to final acceptance.

Legal: Agency legal teams must review and approve contracts in a timely manner and procurement professionals perform the actual acquisition, and either of these can cause delays in awarding contracts if personnel are not familiar with the EPC process.

Technical: Technical oversight is often needed to make sure the project is right for the agency/building and that it is a good investment for the taxpayers. Entities may choose to hire an independent 3rd party to provide technical review of an ESP’s work. - How risky is Energy Performance Contracting for me?

Risks for EPC exist for both the ESP and the entity. Managing those risks includes being aware of the risks as well as mitigating the risks through contract negotiation. Using the documents provided by DEQ and modifying these through your legal staff will reduce your risk. Understand that the savings guarantee only applies to cost-saving measures specified in the contract. The main risk for the ESP is the performance of the project – that the guaranteed savings are realized. If energy savings don't materialize, the ESP pays the difference, not you. - What can I do to get started?

Act today and get those energy savings working for you by reviewing our 5-step process.

- Why use a Request for Qualifications (RFQ) to create a qualified list of proposers?

Statute requires that the entity solicit proposals from at least three qualified ESPs. An RFQ lets you comprehensively survey and quickly evaluate ESP capabilities and experience. It is less risky and less costly for ESPs to respond to an RFQ because there is no requirement for them to spend time on-site. It is helpful to disclose in the RFQ the economic potential of projects for which the agency intends to issue an RFP so that ESPs have an incentive to respond to the RFQ. - What are the distinguishing qualities of the most innovative ESPs?

The most innovative ESPs typically have very experienced energy engineers on their staff. They excel at providing creative and comprehensive design engineering solutions for projects. They are responsive to their customers and provide high quality customer services. They are committed to long-term, sustainable savings performance for their customers and offer continuous project commissioning as a core competency. They have the technical breadth and depth to earn Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) accreditation for their clients and are sophisticated about measuring improvements in indoor environmental quality and accounting for the environmental benefits of reduced air pollution. - How is an investment grade energy audit (IGA) conducted by an ESP different from a traditional energy savings analysis?

Since an Investment Grade Audit (IGA) is the technical and economic foundation for a project that must produce guaranteed energy savings, it typically provides more detail on existing consumption levels, operating hours, and utility costs than a traditional energy analysis. It establishes and defines consumption and cost baselines for all operating costs savings. It also provides a description of the analysis methods, data logger measurements, savings calculations, and all of the detailed technical and economic assumptions used to calculate savings. The IGA serves as the technical basis for project development and justifies the economic feasibility of the project to secure financing. - What are allowable avoided costs in EPC?

Utility cost savings from reduced consumption of energy and are allowable avoided costs. In addition, avoided operations and maintenance costs and avoided equipment replacement costs, to the extent that these agreed upon by the entity, are also allowed. All guaranteed savings must be measurable.

- What is included in an energy performance contract?

An energy performance contract is the core agreement for the project. The Investment Grade Audit Report is the base for project scope as it identifies the cost-saving measures to be included in the project. The contract also includes the cost of the project (often a guaranteed maximum price), payment schedule, savings guarantee, baseline conditions and methodology for adjusting the baseline, methodology for measurement and verification of savings, and other components, each of which is subject to negotiation by the entity and the ESP. Certain components are required by statute and/or rules, but others are able to be customized for the specific project. - What are the disadvantages of using appropriated capital improvement funds for energy efficiency projects?

Capital funds are usually limited so energy efficiency projects face stiff competition from other budget priorities. The approval process for requesting new capital appropriations can be time consuming and expensive. Failure to obtain all the required capital funds for a comprehensive energy improvement project leads to piecemeal project implementation which can be more expensive. The crucial advantage of EPCs is that they use operating cost savings from existing budgets to pay for the financed cost of capital projects. - What are the most important factors to evaluate when reviewing the projected cash flow for an EPC project?

The accuracy, reasonableness, and documentation of utility and other operational savings amounts, are critical to a proper economic analysis. The interest rate and utility escalation rates have a significant effect on the project cash flow due to the length of these contracts (e.g. 20 years). It is important to be realistic, since choosing rates which are too high or low can skew the economic analysis of project feasibility. Also it is important to evaluate the difference between the level of savings being guaranteed and what is projected. For example, if the guaranteed savings are less than 90% of projected savings, it may raise concerns about the accuracy of savings calculations. If guaranteed savings are 100% of projected savings, there should be a significant amount of excess net savings in the cash flow to hedge project performance risk. These differences are also called project contingencies. Both the ESP and the entity may assign a contingency to the project finance package. - Can entities do multiple separate EPC projects on one facility?

Yes, they can. Of course, subsequent EPCs will have to address buildings and/or systems that were not addressed in the original EPC. For example, a large military base may phase its EPCs by area, addressing buildings in one area in the first phase, and another area in the second. Alternately, the entity may choose to lump multiple projects together; however, rules apply.

- How is project commissioning relevant to EPC projects?

Formal building commissioning is a systematic, interactive, and documented quality control process. Commissioning functionally tests and verifies the performance of a building system’s design, installation, operation, and maintenance procedures against the entities cost savings requirements. In the initial commissioning report, the ESP should certify that all newly installed equipment is operating and performing in accordance with the design parameters contained in the commissioning plan. Proper training of building operators and adequate documentation of the building’s systems are also essential components of an effective commissioning plan. The goal, which formal building commissioning shares with energy cost savings performance contracting, is to deliver verifiable building performance results. The commissioning plan should also address a continuous commissioning process to assure the performance of the energy conservation measures (ECMs) over the life of the project. - What are the main benefits of commissioning EPC projects?

Project commissioning provides the knowledge to optimize building equipment system operation for best efficiency. During project construction, commissioning provides more complete communication between the ESP and the entity. This results in shorter punch lists and fewer callbacks, as well as a faster and smoother equipment startup process. Commissioning extends the life of the equipment due to the verification of proper design, installation, and operation. Another valuable benefit from commissioning comes from better building control, which improves thermal comfort and indoor air quality. Again, training of facility staff is an important benefit of commissioning as it ensures that the operational savings will continue over time.

- What are the benefits of measuring and verifying project operating cost savings?

Ongoing measurement of cost savings gives ESPs real feedback on the performance of their design, installation, and operation strategies. Monitoring savings over the contract term improves both the persistence and reliability of savings achieved. Savings measurement and verification helps agencies document the economic benefits of their projects to confirm that cost savings to pay for project financing is being realized. - What is the difference in Measurement & Verification (M&V) options? Where do we find information on them?

The International Performance Measurement and Verification Protocol (IPMVP) offers four options for measuring and verifying performance and energy and water savings. These options, titled A, B, C, and D, are the cornerstones of the standardized set of procedures contained in the IPMVP. In brief, Options A and B focus on the performance of specific measures and require measurement of key factors before and after the project. Option C assesses the energy savings at the whole-facility level by metering and analyzing utility use and costs before and after the implementation of ECMs. Option D is based on computer models of the energy performance of equipment or the whole facility, calibrated against historical utility consumption data to verify the accuracy of the simulation model.

State Guidance Document & IPMVP Public Library of Documents - How can Direct Digital Control (DDC) systems be used to manage EPC project performance?

The following are recommended strategies for using DDC systems to effectively manage project performance:

- Select a system that has energy information data management capabilities.

- Use trend log data to verify equipment operating compliance with energy saving schedules and operating parameters.

- Store trend log data in a data warehouse so that it can be analyzed to refine equipment control strategies.

- Design the trend log data to provide actionable information to building operators and maintenance contractors to optimize equipment performance.

- Use the DDC system effectively for remote equipment operation fault detection and diagnostics.

- Design equipment control alarms so that they are prioritized to provide valuable information.

- Be sure that ESP staff or building maintenance staff is trained to properly use the information provided by the DDC system.

- Establish clear lines of responsibility for who is accountable for taking corrective action based on the data provided by the DDC system.

- What kind of equipment warranties should be expected in EPC?

Typically the ESP will provide a comprehensive equipment and labor warranty for one year from the date of beneficial use of major equipment systems installed as part of an EPC. Due to the fact that construction on large projects can range between 18 and 24 months, it is possible that some warranties could expire prior to completed project construction. It is often possible to negotiate to arrange for the ESP warranty period to run for one year from the date of project completion and acceptance. Specific equipment manufacturer’s warranties do vary significantly based on the type of equipment selected. The ESP should transfer all vendor equipment warranties to the entity. Entities need to do a careful evaluation of the expected value gained from purchasing extended warranties. - What happens if my project is not meeting the savings guarantee?

Although the ESP works diligently to ensure that the guaranteed savings are met, there are instances in which the savings fall short of the guarantee. The EPC contains language on measurement and verification and how adjustments are made to the baseline conditions (e.g. weather, occupancy, schedules). State law requires that the ESP pay the entity:

- The costs of measurement and verification until guaranteed cost savings are achieved for all years in a term of consecutive years equal to the initial monitoring period (minimum of three years); and

- The amount of any verified cost savings shortfall using the baseline rates, plus any escalation rates as allowed by rule.

The entity and ESP may also negotiate terms of measurement and verification reports and shortfall payments for the remainder of the EPC finance term.